Orange & Black ... On Rocky Top about to turn 50

Farragut’s Bobby Scott witnessed, assisted Lester McClain’s football journey breaking UT, SEC color barriers

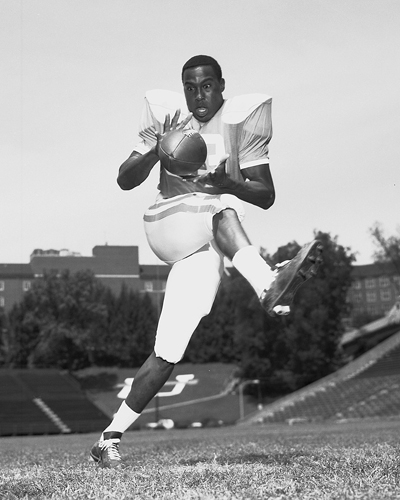

Lester McClain, UT varsity wide receiver, 1968-1970.

Lester McClain, UT varsity wide receiver, 1968-1970.

It marked the first Southeastern Conference football game ever played on artificial turf; the first Vols versus UGA football game in 31 years, and the first UT Football game ever broadcast by now retired “Voice of the Vols” legend John Ward — also a Farragut resident.

But most importantly, it was the first varsity game for sophomore wide receiver Lester McClain — the first African-American UT Football player and one of the first three black athletes in Vols history.

During Black History Month, and coming up on the 50th anniversary of McClain’s first UT varsity game, both men looked back upon Big Orange history — which also became SEC history.

Though “Kentucky had two [African-American] guys who came in ahead of me,” neither finished a complete season according to McClain.

As a result, “I was the only black guy [in the SEC] who played every game in 1968 … and the first black football player to actually letter in the SEC,” added the former State Farm agent in Knoxville, and most recently Nashville, who came from the mid-state as a teenager to help break the school’s athletic color barrier.

McClain, who went on to earn Honorable Mention All-SEC honors during a three-year UT career, contributed to a Vols rally to earn a 17-17 tie with the Bulldogs that groundbreaking afternoon in 1968.

“When I think about Lester McClain, I think about a kid who was hard working. … There wasn’t anybody who was going to outwork Lester,” Scott said. “He didn’t expect anybody to give him anything. He wanted to earn it.

“If I wanted to go out 20 minutes early before practice and get some extra throwing in, or if I wanted to wait until after practice and get 30 minutes of extra throwing in, he was the first one in line,” he added.

“I thought we were good teammates,” McClain said about Scott, adding with a laugh, “I always liked it when he threw it to me.”

Overall, “I had a great relationship with him,” Scott, a sales representative with Balfour, said about McClain. “… He also was a great guy; he was somebody you enjoyed being around.”

The Scott-to-McClain connection helped the Vols compile a 20-3 record in two seasons, including the 1969 SEC championship.

Also led by All-SEC running back Curt Watson during McClain’s last two seasons, The Vols would “run big plays offensively in the pass game from play-action passing. … We were not a team that dropped back and threw it on a regular basis,” he said.

However, against Memphis State in 1969, McClain recalled being Scott’s recipient “of the longest pass in Tennessee history,” covering 82 yards for a touchdown. “Of course, it’s been broken several times since then.”

Recalling specific games where the pair connected in critical situations, Scott pointed to the 1970 game versus UCLA in Neyland Stadium — helping the Vols finish fourth in the nation with a final 11-1 record.

“We had a fourth-down conversion, and I threw the ball to Lester on a hook pattern on the left side for about 15 yards, and made a first down that keep a drive alive,” leading a late-game victory, Scott said.

Beating Air Force decisively in the 1971 Sugar Bowl, in their last game as a UT pass-catch duo, Scott recalled a “no yards” play.

Ironically, the very throw that caught the attention “of the head scout of the New Orleans Saints that drafted me” — Scott going on to serve as Archie Manning’s back-up quarterback with the NFL’s Saints for almost 10 years — was a “deep throw” that McClain dropped.

“It just went right through his hands, the throws couldn’t have been any better,” Scott said with a laugh. “He came back to the huddle laughing, and I got tickled, too.”

By the time McClain and Scott’s careers ended, they were part of a senior class to enjoy two distinctions especially noteworthy in 2018: “We never lost to Alabama,” Scott said. “And we never lost a game in Neyland Stadium.”

However, there would be another athletic bonding event.

“We had a basketball team. To make a little extra money we would go around” the Knox metro area and play pick-up fundraising games, Scott said about himself and McClain plus ex-Vols including Chip Kell, Joe Thompson and Mike Bevins among “a bunch of us.”

“We’d load up in a car and would go to Sweetwater, and we would play their [high school] faculty or their coaching staff or something as a fundraiser, and they would pay us part of the gate,” Scott added. “We had a blast doing it. We met a lot of people in East Tennessee that we would never have gotten to meet.”

Other locations included going as far as “a road trip to Jackson, Tennessee,” he said.

Scott said he didn’t remember witnessing any racist incidents or comments on any of the community basketball visits, “or the whole team would have walked off the court,” he added. “We backed Lester with everything that we had.”

“I guess I took things in stride,” McClain said about dealing with racial tensions on campus. “I knew what I was there to do. I didn’t really do a lot of things away from campus with the guys that were teammates.”

As for acts of racism he encountered, “There were tough things and tough times, but I never dwelled on any of that,” he said.

About choosing UT, “I thought it was a great opportunity. Why not?” McClain said.

Looking back on his freshman year at Haynes High School, a predominant black high school in Nashville in 1963, “around you you’re looking at marches and demonstrations taking place; you knew change was coming,” McClain said.

“… When I was a [rising] senior, I had the choice of continuing at the same high school I had been attending, or changing high schools,” he added.

Transferring to Antioch High School, “a [previously] totally white high school. … That also gave me exposure because Tennessee wouldn’t have known who I was.”

Also a running back, defensive end and cornerback at Antioch as a senior, “as far as having great statistics as a receiver, I didn’t have that,” McClain said. “… I had good speed but I didn’t run [track] sprints or anything.”

As for former teammates at Haynes, “I was the only one out of the group, it seems like, who got the opportunity to go to a major college,” he said.

“That had a lot to do with a gentleman by the name of Bill Garrett,” a UT alumnae who “was a pharmacist, and I guess you could call him a politician as well,” McClain added.

Also involved in Antioch football’s conditioning program, Garrett “came along at a time when you had alumni recruiting for the University of Tennessee,” he said. “Bill Garrett happened to be running the kids at Antioch and also recruiting for the University of Tennessee. … They knew [head] coach [Doug] Dickey. … I used to visit him at the drug store. As time progressed, he thought I was a very good prospect and made it known to coach Dickey and others.”

Just prior to Garrett’s involvement, “I don’t think Tennessee thought much of me as a prospect,” McClain said. “They were recruiting Albert Davis at that time,” an African-American All-state running back at Alcoa High School.

Looking for another African-American football star who would room with Davis, he said, “When everyone else that Tennessee wanted to sign to be a roommate for Albert Davis turned them down, then the only one left standing was me.”

Davis, however, ended up signing with Michigan State — but eventually landed at Tennessee State University, a predominantly African-American university in Nashville.

Because Davis didn’t come to UT, leaving McClain with a white roommate his freshman year, “Many of the writers said we ‘definitely had the first time of total integration’” at the school, he recalled.

Jim Maxwell, a freshman quarterback from Donelson who would become Tennessee’s starting quarterback as a redshirt senior in 1971, was McClain’s white freshman roommate.

“I have had a lot of admiration over the years for Jim Maxwell because that was a tough time for him,” he said. “He didn’t bargain for that — but we got along fine, we never had a problem.”

Overall at UT, “It was great [considering] the ups and downs and the hardships one would have to go through,” McClain said. “I look back quite fondly at that time. I’m appreciative of the good and the bad that I experienced because it’s made such an impact on my life and how to deal with life.

“After awhile it didn’t matter if you were Japanese, Black, Chinese or whatever; once everyone decided you could play that’s all that counted,” he added.

McClain and wife, Virginia, have two children.