The legend of Thunder Road

About the mountain boy who ran illegal alcohol

His daddy made the whiskey, son, he drove the load

When his engine roared,

They called the highway

Thunder Road.

Sometimes into Ashville,

sometimes Memphis town

The revenoors chased him but they couldn't run him

Down

Each time they thought they

had him,

His engine would explode

He'd go by like they were standin' still on Thunder

Road.

(Chorus);

“And there was thunder, thunder over Thunder Road

Thunder was his engine, and white lightning was his

Load

There was moonshine, moonshine to quench the devil's thirst

The law they swore they'd get him, but the devil got

Him first.

On the first of April, nineteen fifty-four

A federal man sent word he'd better make his run no

More

He said two hundred agents were coverin' the state

Whichever road he tried to take, they'd get him sure as

Fate.

Son, his daddy told him, make this run your last

Your tank is filled with hundred-proof,

You're all tuned up and gassed

Now, don't take any chances, if you can't get through

I'd rather have you back again than all that mountain

Dew

(Chorus);

“Roarin' out of Harlan, revving' up his mill

He shot the gap at Cumberland,

And screamed by Maynordsville

With G-men on his taillights, roadblocks up ahead

The mountain boy took roads that even angels feared

To tread.

“Blazing' right through Knoxville, out on Kingston Pike

Then right outside of Bearden, there they made the fatal

Strike

He left the road at ninety, that's all there is to say

The devil got the moonshine and the mountain boy

That day,"

— “Thunder Road” song lyrics

More than 60 years ago, a Hollywood movie and chart-topping song highlighted the dangers of moonshining up close for the world to see.

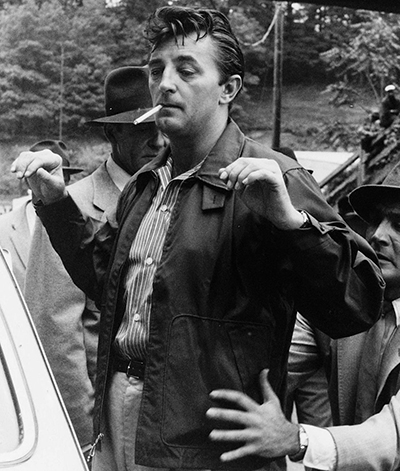

“Thunder Road,” starring legendary actor Robert Mitchum — who also wrote the 1958 movie and helped craft the song — told a tale of bootleggers who tangled with the law, with one horrifically losing his life in the process while running “white lightening.”

While Mitchum fictionalized his own character’s backstory, “Thunder Road” was a well-known moonshine route that ran from Kentucky, through Maynardville, then into Knoxville on what is now Kingston Pike, and he incorporated a legendary car crash that disputably occurred either in Bearden, near Asheville Highway or in Concord (now Farragut), depending on who is talking.

While no newspaper accounts have been found to verify the story, several members of the community have gone on record with their accounts.

Knoxville-area writers Laura Tedesco and Brooks Smith both conducted extensive research about the infamous incident, publishing lengthy articles on their findings. They also relied on “Return to Thunder Road,” a book written by Alex Gabbard, who interviewed a young eye-witness, John Fitzgerald, among others.

The teen recalled encountering suit-and-tie governmental officials at a local service station early one April morning in the early 1950’s, overhearing whispered mentions of “Thunder Road.”

The following is Tedasco’s account, reprinted with permission:

“That cool spring morning, John and his friends had inadvertently stumbled upon a federal operation to capture a notorious Kentucky moonshiner known only as “Tweedle-o-twill,” Tedesco wrote.

“In the early morning hours, just down the Pike from Galyon's (gas station), Tweedle-o-twill, the son of an elusive mountain moonshiner, was racing against time,” Tedesco wrote. “As the sun peeked through the trees, he rocketed down the highway, sweeping across the last leg of his journey down Route 33 from Kentucky through Maynardville and into Bearden.

“Federal agents devised a makeshift roadblock, two cars nudged nose-to-nose across the two-lane highway. They parked their fleet of vehicles in the cedar-lined driveway of a roadside farm and waited.

“But as Tweedle-o-twill raced toward them at 90 miles an hour, it became apparent that he had no intention of stopping. He flew off the road, crashing over fences and infant trees, evading the roadblock and barreling past the agents unhampered.

“After clearing the first roadblock, Tweedle-o-twill roared down Kingston Pike, unaware that a second roadblock, a row of cars bumper to bumper, was aligned at the intersection of Morrell Road and Kingston Pike. John and his friends watched from a nearby farmhouse, located on the present-day site of West Town Mall.

“Rocketing around the bend, he lost control, sending the car into a dirt bank bordering what is today the parking lot of where Cat’s Music was once located,” Tedasco wrote. “The high-speed collision whipped up a cloud of red clay dust visible from the second roadblock. As the federal agents raced to

the scene, John pedaled down Kingston Pike to catch a glimpse of the accident that would become legendary.

“As the car launched through the fence of a roadside utilities substation, its trunk sprung open, shattered jars of whiskey seeping their contents amidst the electrical equipment. John watched as the substation burst into flames, the smell of whiskey strong and biting.

"I remember looking at the driver and thinking, 'What a waste,'" John told Gabbard. ‘He gave his life for a trunk of whiskey.’”

Others had similar stories, including Edward “Eddie” Harvey, a former race car driver, whisky car mechanic and owner of Eddie’s Body Shop in North Knoxville, who shared the tragic ending of Rufe Gunter with Tedasco.

“Rufe … was coming from Newport to Knoxville,” Harvey told her. “Somebody had ratted on him.

"When Rufe found out, he bought an old car, an old Studebaker, and loaded it down. He thought the law wouldn't know him."

But as the moonshine runner neared Knoxville, “just outside the city limits at Swann Bridge on Highway 70, the police began tailing him, determined to catch the Newport outlaw.”

In his mission to outrun the law, Gunter reportedly lost control of his car, struck a tree stump and the vehicle ended up in the Holston River, along with 20 cases of whiskey.

"The law never did stop," Harvey said. "I went up there and I found him hanging on a limb in the creek, drowned."

Smith’s interviews and investigations into the legend took him down very similar roads. In his own writings, he mentioned Fitzgerald, describing him as “a Farragut farmer” who “went to his grave swearing, absolutely believing, and persuading many others that he saw with his own eyes that car swerve off Kingston Pike and into a Lenoir City Utilities Board switching station.”

Smith also detailed exhaustive research fellow freelance writer Kate Clabough made, investigating the “true story” on which the movie was ultimately based.

“Clabough checked newspaper microfilms, police reports and funeral home records,” Smith wrote. “From the very beginning, Grant McGarity, longtime head of the Knoxville office of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, told Clabough he had always heard the real subject of Mitchum’s movie was from Cocke County.

“This was logical, since Newport had for many years been the nation’s capital of moonshining,” Smith added.

“Following that lead, Clabough sent a letter to the editor of The Newport Plain Talk. It was a short note, saying she was looking for the identity of the person in the movie Thunder Road.

“Within days, Clabough received an unsigned letter, written on two sides of lined notebook paper in a neat script, probably that of an elderly woman. It was postmarked Knoxville. It said the facts, “as told by my mother,” were that “the person in Thunder Road was from Mountain Rest in Upper Cosby, now in the National Park. Pinkney Gunter was a maker of moonshine. His son, Rufus, was the ‘runner’ and delivery man.

“After Rufus’ death," the letter continued, “The family was approached by Mitchum’s people about signing a release to make a movie based on their son’s exploits. At first, his father refused, but eventually his mother did sign the release.”

Then Clabough got a call from Cocke County Circuit Court Judge Ben Hooper. “Thunder Road was based on a man named Rufus Gunter,” Hooper further confirmed to Clabough. “He didn’t die like Mitchum’s character, but he certainly lived like him.”

Hooper said in January 1953, Gunter was being chased on the Asheville Highway, heading toward Knoxville, when he got to the J. Will Taylor Bridge.

Harvey, who also was interviewed by Fred Brown of the Knoxville News Sentinel, reiterated the details for that journalist.

"It was ice cold and Rufe was red hot from driving that car,” he told Brown. “He jumped for it. When he hit the water, he took a cramp and went under. It took me a week to find him."

“The words of Mitchum’s song are so vivid — and tied to the roads we drive every day — that in our minds many of us have seen that Ford Coupe leave the Kingston Pike at 90 and flip into that switching station a hundred times,” Smith wrote.

Site still questioned

However, Larry Bowers, staff writer and former editor for the Cleveland Banner, wrote a column in 2016 in which he challenged the long-standing legend of the alleged crash site.

“My memories, and information and I have received since (the purported crash), contradict the location of the actual crash ... if there was a crash. Many think the story is fictional, but others who lived in West Knoxville and surrounding communities claim it is real.

“I worked and spent considerable time in West Knoxville in the late 1980s and early 1990s. More than one person told me there was an actual crash, but they say it wasn’t on Bearden Hill. They say it happened at a power line substation at the intersection of Watt Road and Kingston Pike — about 2 miles beyond the Willow Creek and Fox Den golf courses in Farragut.

“It is an inconvenient truth that there is no record of a crash involving a moonshiner on or around April 1, 1954. That would have been too easy. Still, old-time residents of Farragut remember such a crash. This could be wishful thinking on their part, but all of the stories I’ve been told are very similar,” Bowers wrote.

“Regardless of which story is true, or not true, the ‘Thunder Road’ film, and its accompanying ballad, have become legends since they were released in the 1950s.

“The sad thing about the whole scenario is, if the story is true, no one knows the identity of “the mountain boy” who died in the tragic crash," Bowers added.

“With that in mind, it would be best to think the story is all fiction.”